CMYK

I am making a-game-a-week(ish).

These will be short prototypes, very unpolished, probably broken.

A Sokoban-style game next. Based upon the CMYK subtractive color model.

- Made in ~8 hours using PuzzleScript

- Source Code

Notes:

The game:

The decision to try out PuzzleScript this week came first, so I was immediately faced with the prospect of having to design a puzzle game. Having absolutely no idea how to even start designing a puzzle game, the 'made in' estimate above should probably include another couple of hours spent just doodling ideas whilst otherwise marking exam papers, before I even had any clue what direction to take...

I started with a vague notion of a theme of 'pirates'; something about finding treasure. This did not lend itself to anything obvious in terms of game mechanics. After mulling over a number of possible themes, I realised that unless a theme had a really obvious mechanic that tumbled out of it, that was not the way to go about designing a puzzle game; I needed a core mechanic. So I gave up, and thought 'I'll just make a maze game' of some kind. My very first idea was the kind of "loops and traps" stye maze (similar to the 'red doors' maze from The Crystal Maze)

Actual inspiration came from the printer at work; it needed new ink, and as I was looking for a new cartridge, I noticed the colours were Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and blacK (CMYK). I'd seen this before for in printing, and wondered why screens used an RGB system but printing used CMYK. A little read of Wikipedia later and I had my mechanic: A maze game with 'logic gates' where colour was subtracted from the player.

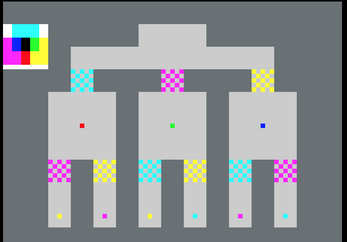

Turns out, mazes are really dull. And super easy to solve, especially if you can just see the whole thing, and inventing difficult or interesting mazes was a challenge. Without moving the whole thing to DungeonScript (a fork of PuzzleScript that runs in a first person view), I needed something more than mazes and gates and things to collect. So I caved in and added blocks. Turns out, this made making puzzle so much easier; with the layer of complexity that subtracting colour fields adds, even simple block pushing puzzles became tricky enough to call challenges.

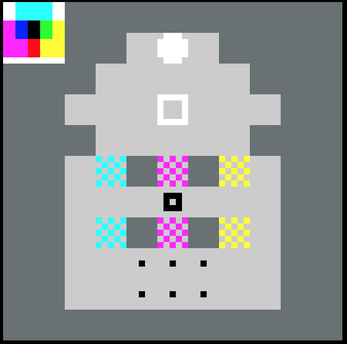

I'm not sure that the core mechanic is a particularly good idea, in the end. It involves trying to remember a 'tree' of cascading colour subtraction so that you can work out how to take a white block. The earlier puzzles need to spend far too long teaching this core mechanic, and in the later puzzles, I tried to avoid creating levels where the primary challenge was simply remembering how to move from one colour to another. The diagram was supposed to work as an aid, but more serves to show just how overly complex this design is. The super-flat art style is a product of placeholder design that I never got around to updating, and ended up quite licking anyway in the end. The ability to shove blocks past a field when the player can't follow started out as a bug in the code, but turned out to be the only way to make solvable puzzles that weren't super simple, so it stays in, even if a bit unintuitive.

The engine:

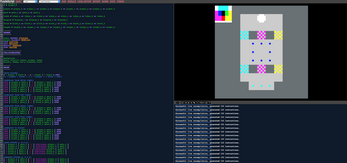

PuzzleScript is the first text-based coding used in this series. It presents as a area to edit code on the left, with the play-space and output logs on the right. It's language, however, is quite unusual. The code itself is built from very specific section; a list of objects (and their drawing as 5x5 blocks), sounds, collision layers, rules and levels. Importantly, for novice developers, all of these sections, apart from rules, are entirely descriptive. For example, levels are simply a grid of letters, numbers and other characters, each character being a square on the grid of the level as it will appear, and each character representative of an object (or layer of objects) as defined in the 'Legend' section. Levels can be immediately loaded by simply Ctrl+click-ing them, and there's even an in-built level editor for easier editing.

The 'Rules'' section in the only 'proper' bit of coding that PuzzleScript uses. It is, however, based upon description, like rest of the system. Fundamentally, it is primarily made from 'IF' statements, albeit not using that statement. Every single rule has a condition on the left hand side that the game 'looks' for at the end of each move (or per user-defined time period, if you set the game to be realtime) and, on the right-hand side, what will occur if that condition is found.

For example, there is no 'red' in a cyan coloured player object. So cyan fields need to stop red players. It looks like this:

[ > player_r | gate_c ] -> [ stationary player_r | gate_c ]

On the left, it looks for a RED player moving towards a CYAN field (gate). The vertical bar means adjacency, the '>' refers to relative movement (the player moving forwards, into an adjacent gate). The result simply stops the player moving by marking it stationary. The most simply Sokoban-style games can be built from just one rule. CMYK in built from a bit over 50 rules. However, many of these are duplicates to account for the various colours. Without these colours, there would just be four rules.

| Status | Released |

| Platforms | HTML5 |

| Rating | Rated 5.0 out of 5 stars (2 total ratings) |

| Author | Nick |

| Genre | Puzzle |

| Made with | PuzzleScript |

| Tags | blocks, Colorful, PuzzleScript, Sokoban |

| Code license | GNU General Public License v3.0 (GPL) |

| Asset license | Creative Commons Attribution_NonCommercial_ShareAlike v4.0 International |

| Average session | A few seconds |

| Inputs | Keyboard |

| Links | Twitter/X |

Development log

- Updated final levelMay 24, 2018